Russel hails US ‘position of strength,’ Odell says ‘dangerous to oversimplify’

Historians may look back at the U.S.-China meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, last week as a pivotal moment in geopolitics — when a rising power and a ruling power sat across the table and debated whose view of international order was right.

The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden is committed to «strengthen the rules-based international order,» Secretary of State Antony Blinken said. He noted that China’s actions in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan «threaten the rules-based order that maintains global stability.»

China’s top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, shot back. «What China and the international community follow or uphold is the United Nations-centered international system and the international order underpinned by international law, not what is advocated by a small number of countries of the so-called rules-based international order.»

Daniel Russel, former assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs under President Barack Obama, says it was important that Blinken met with allies before the Alaska meeting and went into the talks from a position of strength.

Rachel Esplin Odell, a research fellow in the East Asia Program at the Quincy Institute, says no such version of a world order has ever existed, and it is dangerous for the U.S. to oversimplify the structure of the debate.

Edited excerpts from their interviews follow.

Daniel Russel, left, and Rachel Esplin Odell.

Daniel Russel, vice president for international security and diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute

Q: How did you observe the Anchorage meeting, including the heated on-camera exchange between the U.S. and China?

Russel: What was important wasn’t that acrimonious exchange at the beginning of the meeting. Even though that’s obviously where the drama was — in part because the cameras were rolling — that wasn’t what was important. What was important about this meeting was that it came only after the Biden administration had already held a Quad summit. It came only after holding a two-plus-two, in Tokyo and then in Seoul. It came only after setting a date so that the Japanese prime minister could be the very first foreign leader to be received by the new president in the Oval Office.

That’s the context that matters. The Biden administration did not try to have a direct dialogue with the Chinese until they had already done these other things.

On top of that, they scheduled the meeting with the Chinese after Biden successfully passed his $1.9 trillion budget, his relief bill, after he accelerated vaccine distribution in the U.S., making it clear that we’re being successful, after he took some steps to address racial tensions, Black Lives Matter, anti-Asian violence, and so on.

So the point is he is showing, and the Chinese can see, that the U.S. is now beginning to deal effectively with problems that were mishandled over the past four years. So, that is what Biden means by dealing with China from a position of strength. It’s not only military strength; it’s international partnerships and it’s American society and the American economy back on a positive trajectory.

Q: What was the Chinese take on this meeting? They accepted an arrangement to meet on U.S. soil. Before this meeting, the Chinese side had indicated that this was a high-level strategic dialogue, which the U.S. side rejected.

Russel: The Chinese always want to have a very visible and structured dialogue with the U.S., but they usually want it for the wrong reasons. In the past, they have used these dialogues to buy time and to give the false impression that the problems were being solved.

They have an unlimited number of talking points. They can talk for hours. But that’s not the same as accomplishing anything or resolving anything.

As far as the international community and other countries go, international polls show that there is deep-seated suspicion and unease towards China, including among countries that don’t have a border dispute or don’t have a particular bilateral problem with China.

My opinion, though, is that most of these countries also want to see the U.S. combining firmness in dealing with China but also cooperation.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, accompanied by national security adviser Jake Sullivan, right, talks to the media after a closed-door morning session of U.S.-China talks in Anchorage, Alaska on March 19. © AP

Q: Are you concerned that if the U.S. presses China too much, there will be little cooperation on global issues such as climate change and COVID-19?

Russel: The risk was that China would trade cooperation on global issues that are important to both of us, in exchange for the U.S. recognizing what China calls its «core interests.» That is not a trade that the U.S. should make, and I’m happy to say it’s not a trade that the Biden administration would accept.

China doesn’t have the right to unilaterally declare that no one can talk about its mistreatment of its own ethnic minorities. China is a member of the U.N. and acceded to the U.N. Charter. It signed the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights. Human rights standards are universal principles.

Similarly, China doesn’t have the right to say, «Oh, the South China Sea is our territory. This is a core interest. You can’t disagree with us, you can’t challenge us.» Or, in the East China Sea as well.

The U.S. is not willing to stay quiet about behavior by China that threatens regional stability, or that violates global norms, in exchange for Chinese cooperation on climate change or on COVID-19 or anything like that.

But, it doesn’t mean that we can’t have both. In the past, I remember Japanese colleagues talking about how the economic relationship could be warm, while the political relationship was cold.

There are many examples in the history of the U.S.-China relationship where we had a very serious disagreement on one set of issues but we were able to cooperate on another issue. For example, when I was in government, the U.S. sold $11 billion in arms to Taiwan, and negotiated successfully the U.S.-China Climate Agreement.

With skill and good diplomacy, we know that it can be done. It has been done in the past.

Today, however, it may be much more difficult.

China is stronger. China is more confident. China is richer. China has more global influence. And China’s leader is a much more aggressive leader. And, the U.S. is in a weaker position, today, than it was five years ago. I’m not saying that it’s easy but I am saying that it’s possible.

Q: Some might say that Biden has less leverage over China compared with what Trump did with tariffs, and that he will find it hard to get China to act on human rights, for example.

Russel: No, I see it a little bit differently.

Donald Trump was very good at creating leverage with China, through tariffs and other measures. It’s true that that was very expensive to the U.S.

But he didn’t care. So, he created a lot of leverage, and there are now in place a lot of measures — sanctions, tariffs, prohibitions, import screening, investment restrictions — that the Chinese very much want to lift. There are many things that they are prohibited from accessing in the U.S., whether it’s technology or access to universities, that they really, really want to have.

Biden has not given up any of that, yet.

Now, many of these restrictions make no sense, or are too extreme. You might want to block a Chinese advanced researcher who is coming to the U.S. to study quantum computing. We don’t want to help them compete against us.

But, that’s very different from stopping an undergraduate Chinese who wants to come to Harvard and study engineering.

What the review that the U.S. government is now undertaking aims to do is to figure out which of the measures that were created in the Trump administration do we want to keep, which ones do we want to adjust, and which ones do we want to eliminate.

The next step is to take the sanctions and the measures that we don’t feel like are helpful to us and use those as trading material in negotiations with China. You don’t just give it away. It’s valuable.

From left: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, Politburo member Yang Jiechi, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and national security adviser Jake Sullivan. Their combative meeting last week in Alaska surprised China’s leadership and leaves Beijing searching for a way to stabilize relations. (Source photos by Reuters)

Rachel Esplin Odell, research fellow in the East Asia program at the Quincy Institute

Q: At the Alaska meeting, Blinken told Yang that after speaking with nearly a hundred counterparts from around the world, he is hearing deep satisfaction that the U.S. is back, and that there is deep concern about some of the actions the Chinese government has taken. He signaled that there is a united front against China.

Odell: I think that’s an oversimplification of a more complex reality. Who is united? It’s always fraught to say who stands with the U.S. in terms of attitudes towards China. Every country has complex and varying relations with China.

This is even the case with Japan, perhaps the most natural U.S. partner in adopting a more competitive or confrontational approach vis-a-vis China. China-Japan relations are very significant and important and in many ways China and Japan have sought to limit the acute adversarialism in their relationship over the last many years.

If you look at a number of other powers that Blinken is lumping into that category, you see it’s more complex. This is the case with the European Union. Germany and France have made it quite clear that they intend to adopt their own strategic posture towards China. Germany pushed through that EU-China investment deal right before the Biden administration came into office, even though [soon-to-be national security adviser] Jake Sullivan made it quite clear that he wanted them to wait.

Of course at these EU- or NATO-U.S. meetings they welcome statements about America being back, that’s a breath of fresh air relative to Donald Trump from their perspective. But I think that they recognize that in some areas, U.S.- European interests may not always align and that perhaps China is one of those.

French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and then-European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker welcome Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Elysee Palace in Paris on March 26, 2019. © Reuters

I do think that what Blinken is probably hearing in these meetings is that these countries have concerns about China, that they do feel like over the last year or so, China’s behavior, for example the cyberattacks in Australia and what is happening on the Indian border, has been quite more belligerent than it has in the past. I think all of these are sources of real concern. So China needs to rethink its diplomacy if it wants to enhance its relations with other countries. But I also think it’s not so simple as, the rest of the world wants to unite with the U.S. to push back on China.

Q: You have written that oversimplifying could be dangerous. In what way?

Odell: The most pressing threat facing the world and the U.S. at present is the global COVID-19 pandemic, as well as potential future pandemics. Scientists have made clear there, there could be pandemics that could be even worse than this one. Climate change also poses a serious, existential threat to the world.

If we portray China as a threat to the rules-based global order, which is the dominant rhetorical theme in U.S. comments on China, then it really risks preventing the kind of cooperation that would be necessary in some aspects of that world order, because that rhetoric becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that dampens enthusiasm for engagement with China in the U.S.

On the flip side, if we are portraying China as a threat, we could foreclose the type of crisis communication and confidence building measures that we need to prevent conflict from breaking out in areas where we disagree. If we treat China as an enemy, China will feel like we are an enemy to it, and we’ll respond accordingly, in a vicious spiral that could lead to increased animosity between the two sides and increase the likelihood of conflict over hot spot issues such as in the South China Sea, the East China Sea and over Taiwan.

Q: What is your take of the Obama years and the engagement policy with China? Critics say it only gave China time to grow without having to implement the kind of reforms the U.S. wanted.

Odell: To begin, the goal of U.S. policy shouldn’t be to prevent China from developing economically. China’s rise is not something that the U.S. has a whole lot of unilateral leverage over.

It’s important to realize that facilitating China’s rise in a way that’s peaceful and serves the economic interests of the American people and the world was a goal of U.S. policy, and it succeeded. A lot of the times it’s portrayed as having been a failure and I think that’s a misrepresentation.

That long-standing policy, from the Clinton administration, especially the Bush administration and then the Obama administration, was largely successful and it really reflects a certain myopia when the U.S. expresses regret that China has risen and we could have prevented that. I think that’s unrealistic and also overly zero sum.

Now obviously there have been negative trends in China, particularly in its domestic governance, and it has become more authoritarian over time. China has not liberalized in ways that some Americans, and many Chinese had hoped. But that was a secondary objective of U.S. policy. Particularly in more recent years, the goal of the Obama administration was to facilitate concrete cooperation and progress on a number of issues and they did manage to do that.

In the economic relationship, there were domestic policy failures in the U.S., where we failed to implement the domestic policies that would ensure a fair distribution of the gains from trade with China and other countries. But U.S. trade with China over the past few decades has still been on balance a major driver and facilitator of American economic growth.

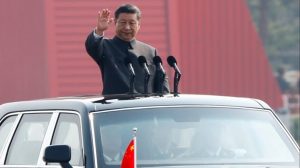

Chinese President Xi Jinping waves from a vehicle as he reviews the troops at a military parade marking the 70th founding anniversary of the People’s Republic of China on Oct. 1, 2019. © Reuters

Odell: That is probably an overstatement and an exaggeration of China’s intentions vis-a-vis Taiwan. Of course their deeply held aspiration is what they would describe as reunification with Taiwan. But just because they hold that as an aspiration, it doesn’t mean that there are imminent plans to put that into place.

The Chinese government recognizes that any attempt to invade Taiwan or engage in major military operations against Taiwan would be very difficult for them to win and to achieve success. It would have dramatic negative consequences for them economically and diplomatically, and if they were actually to try to invade Taiwan, there would be risks of facing long-term insurgency resistance and this would be extremely costly.

So this isn’t something that they’re likely to engage in, even if they have what you might call overmatch.

There could be more limited ways they may seek to engage in measures to coerce Taiwan, perhaps through seizing some of the Taiwan islands that are right off the mainland, or maybe through some sort of a blockade strategy. But even those would not guarantee a long-term positive outcome for China. In the eyes of the Chinese government, their preference would be to achieve eventual peaceful reunification.

All that said, I do think there are ways in which trends are changing, in Taiwan, and across the strait, in ways that China is not sufficiently adapting to. It is not being very pragmatic and thus, we could through an action-reaction dynamic escalate to conflict.

Attitudes in Taiwan toward unification have soured in recent years, while attitudes favoring eventual independence have strengthened. But the majority of people on Taiwan favor some maintenance of the status quo, even if more of them now want eventual independence. I would say that [Taiwan’s President] Tsai Ing-wen is relatively pragmatic in this regard and doesn’t want to push for immediate independence.

And if China doesn’t have a pretext, such as a declaration of independence by Taiwan, they’re very unlikely to invade.

But all of this is built, in part, upon the long-standing position, which is that the U.S. would not oppose the peaceful unification of the two sides if it was mutually agreed upon. There is concern in China that maybe the U.S. is trending away from that position.

The real core of China’s problem is that they aren’t adjusting to these dynamics, other than to send more air operations across the midline and into Taiwan’s ADIZ [air defense identification zone] and refusing to engage with Tsai Ing-wen and the Democratic Progressive Party in ways that I think are very unrealistic and very damaging to China’s position. With what’s happened in Hong Kong, «one country, two systems» is no longer viable in the minds of Taiwan’s people. That framework is a non-starter now, so I think China, if they really want a peaceful «reunification,» should think more about how to adjust their strategy and engage more with the DPP.