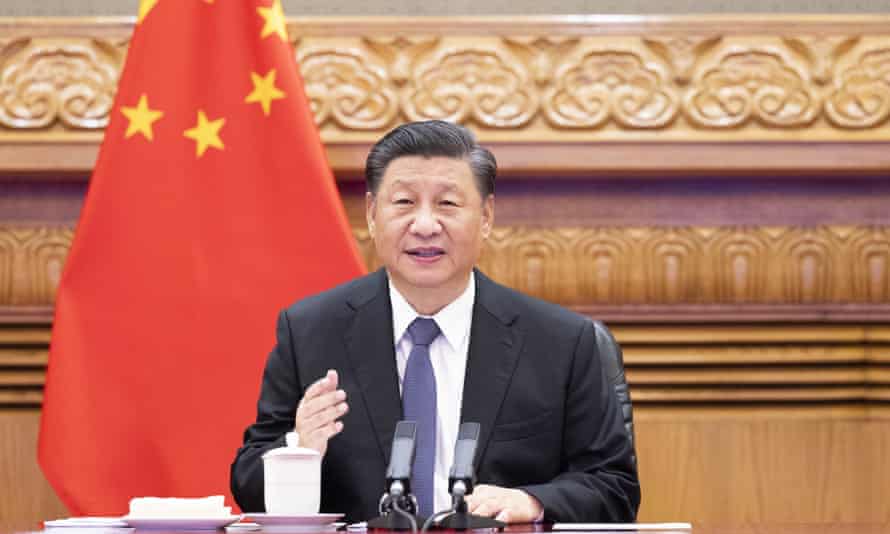

Analysis: Xi Jinping wants his country to appear more lovable, but critics say Beijing’s efforts are too superficial

China’s appointment of a new ambassador to the US has shone a light on the ongoing debate among analysts about how Beijing communicates with its biggest competitor, the future of its “wolf warrior” diplomacy and how Xi Jinping’s call to “tell a good China story” might work in practice.

The debate over the “wolf warrior” style – under which, as the Chinese ambassador to Sweden said on Swedish public radio in 2019, “we treat our friends with fine wine, but for our enemies we have shotguns” – comes amid a burst of positive publicity that delighted Beijing’s propaganda officials: the foreign coverage of the herd of 15 wandering Asian elephants in southern China that captured the country’s imagination and led Chinese vloggers to travel hundreds of miles to take selfies with them.

The foreign coverage led the Global Times to claim that China’s care for elephants “mirrors [our] adorable national image the west can’t distort”.

The odyssey of the travelling elephants came at a time when western media were questioning the effectiveness of Beijing’s strident “wolf warrior” diplomacy.

Foreign journalists have complained about the intensifying government pressure over their work in China. In the past 18 months at least a dozen American journalists have been expelled in a tit-for-tat with Washington. Last week, as severe flooding hit the central province of Henan, correspondents from international outlets – including the BBC, Los Angeles Times, Deutsche Welle, Al Jazeera, CNN, Agence France-Presse and Associated Press – reported harassment by locals who accused them of being “rumour mongers”. Some were physically confronted by angry crowds, while others have been doxed – in which personal information is maliciously spread online – abused, and threatened with violence or death online.

“There is a very real feeling [in Beijing] that China doesn’t get the respect that its leaders think they deserve for the Chinese rejuvenation story. There is a desire to stop others dominating the discussion of China,” said Shaun Breslin, a China expert at the University of Warwick who is also the author of China Risen? Studying Chinese Global Power.

Beijing’s drive to promote positive China stories showed it understood soft power was “just something that great powers have, and it is a measure of China’s level of great-powerness”, he said.

In the weeks since Xi’s comments, officials have begun a nationwide call for ideas on how to tell a good story about China. Critics, however, say without overhauling the confrontational “wolf warrior” style and changing some of Beijing’s controversial policies, these efforts are only superficial, if not counter-productive.

“Comedians talk about the difference between punching up and punching down. If you make a joke about people who are above you – higher status, more powerful etc – then it’s funny. But if you say the same things about people below you it sounds nasty or vicious,” said Breslin.

“I wonder if this is what’s happening with at least some of the people who speak for China. They think they are punching up. But others look at them and think they are punching down.”

It is not only overseas observers who have pointed out the shortcomings of China’s communication strategy, however. In a recent thinktank seminar in Beijing, Chinese experts articulated their concerns over what they describe as Beijing “mirroring internal propaganda in external propaganda”.

Chu Yin of the University of International Relations in Beijing said: “[If ] we use this approach, or adopt the standards of internal propaganda to dominate external one, [we’ll then end up] investing tons in external communication, but only see the effects domestically.”

Chu said the “impetuousness” of the internet era could often make attempts to promote a positive image of China backfire. In order to meet nationalistic sentiment at home, he said some experts and diplomats would “lower their standards”, which would eventually result in “telling the China story well” being hijacked by sentiments on the Chinese internet.

Chu’s criticism is considered vocal in the current political climate in China, but he is far from alone. Last year, Yuan Nansheng, China’s former consul general in San Francisco, cautioned in an article that the “wolf warrior” diplomacy risks replacing dialogue with confrontation, “resulting in China having less and less friends”.

These comments reflect a sense of confusion – or dismay – among those who for years have advised the government on how to communicate effectively with the outside world in order to have China’s perspective heard.

It was a confusion shared by some state media journalists – often labelled as Beijing’s “propagandists” – said Wang Zichen, a former Brussels correspondent for the official news agency Xinhua, now working in its headquarters in Beijing.

Wang became well-known among foreign journalists and diplomats from the early days of the Covid pandemic when he began to produce an occasional newsletter called Pekingnology, which he claimed had since had more than 2,100 subscribers – from foreign diplomats to journalists and China-focused academics.

Twitter also labelled Wang’s account as “China state-affiliated media” last year. He said when he saw the label he was “surprised and dismayed”. “But then, I joked to myself: not everyone can have this badge of honour as a state account, so I began to think of the ways of making the best use of it – including tweeting actively about what I think is the most accurate information about China.

“The current situation is that the west is mostly seeing the side of China it wants to see, and we don’t always speak the language the world easily understands, either. It’s a two-way street,” Wang said, admitting he did not publish much contrary to Beijing’s official stances but still wished to be a “bridge” between China and the west.

Breslin is wary. “It’s really hard to get people to focus on what you want them to focus on. Issues like Xinjiang and Hong Kong create an overarching background that frames the way that people look at China. And we haven’t heard the end of the pandemic in China yet, either,” he said. “What you do can be much more important than what you say.”